|

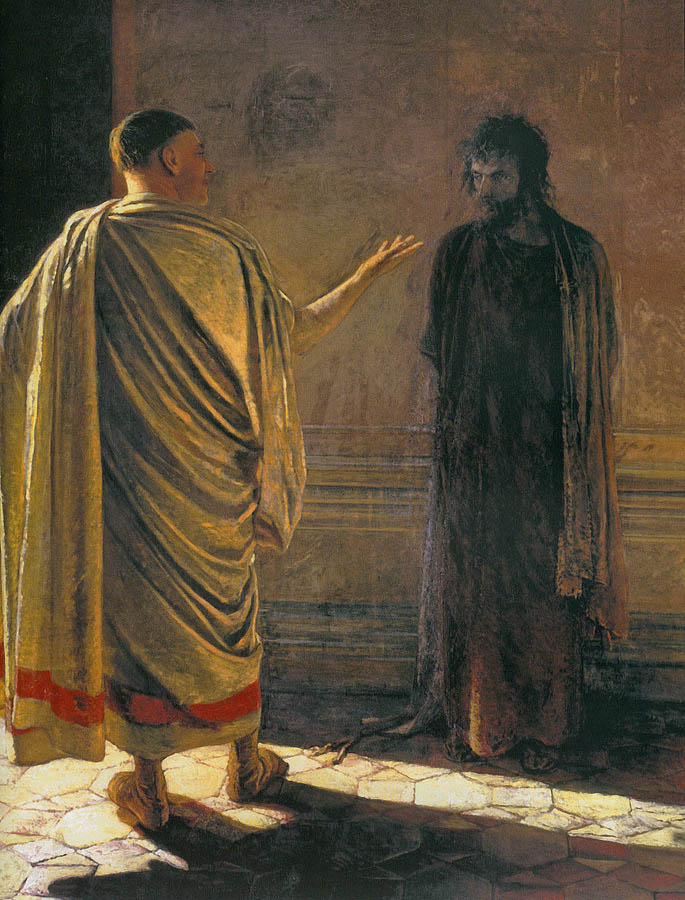

| Quod Est Veritas?, Nikolai Ge, Russian realist |

In Part V, Chapter 9 of Anna Karenina Anna and Vronsky are living together in an "old neglected palazzo" in Italy. It is morning and they have received a visitor. It is Vronsky's friend, Golenishchev.

"Here we live and know nothing of what's going on," Vronsky said to Golenishchev as he came to see him one morning.

"Have you seen Mikhailov's picture?" he said, handing him a Russian paper he had received that morning . . .

"I've seen it," answered Golenishchev. "Of course, he's not without talent, but it's all in a wrong direction. It's all the Ivanov-Strauss-Renan attitude of Christ and to religious painting."

"What is the subject of the picture?" asked Anna.

"Christ before Pilate. Christ is represented as a Jew with all the realism of the new school."

And the question of the subject of the picture having brought him to one of his favorite theories, Golenishchev launched forth into a disquisition on it.

"I can't understand how they can fall into such a gross mistake. Christ always has his definite embodiment in the art of the great masters. And therefore, if they want to depict not God but a revolutionist or a sage, let them take from history a Socrates, a Franklin, a Charlotte Corday, but not Christ. They take the very figure which cannot be taken for their art . . ."******************************************************************************

Christ before PilateThis refers to when Christ stood before Pontius Pilate the Roman Prefect who sentenced Him to execution by crucifixion.

When the morning was come, all the chief priests and elders of the people took counsel against Jesus to put him to death:

And when they had bound him, they led him away, and delivered him to Pontius Pilate the governor.

Matthew 27:1-2The story of the crucifixion of Jesus is found in all four Gospels:

Matthew 27

Mark 15

Luke 23

John 18-19

|

| Head of a Man, Aleksandr, Ivanov, realist painter mentioned in Anna Karenina |

They take the very figure which cannot be taken for their art.

Wherefore, my dearly beloved, flee from idolatry.

I Corinthians 10:14

This part of the passage was confusing to me. I did not understand what was behind Golenishchev's argument. Orthodox Christians use icons, so why would one be offended by a realistic painting of Jesus? I tried to search this online from multiple angles. Sometimes, friends, the search engines fail me and there is no book on my shelf to meet the need.

Last night I thought of my friend Will, who is an Orthodox Christian. He lives several states away. I sent him a private message via Facebook. He replied within minutes. I asked him if he understood what this quote implied. He very kindly took the time to type out the following message from his phone:

Will's insight has whetted my appetite to learn more about the difference between these two views. He wrapped up our conversation with this blessing:

Last night I thought of my friend Will, who is an Orthodox Christian. He lives several states away. I sent him a private message via Facebook. He replied within minutes. I asked him if he understood what this quote implied. He very kindly took the time to type out the following message from his phone:

I think this is the difference between the "iconic" view and the "artistic" view, in which icons intentionally try to allow the viewer to see the reflective and unreal nature of art...

Icons show the reality of the persons themselves, "circumscribing" and commemorating the incarnation, but, by their "unrealism", they point away from themselves and try to maintain the role given to them by the Church - a language for communicating the Gospel, and not as a "real representation", which might lead the viewer to idolatry.

If someone looks at an icon and thinks, "That is Christ", then it is very easy to think that "The Icon is Christ." Icons are nothing on their own, only significant because of the reality they point toward.

In this quote [from Anna Karenina], I think you see the strong Eastern dislike for the "Idolization" of Western art, which necessarily leads to a reaction, iconoclasm, which is the realization that the art is not what it represents.

After the representation has been taken to be "the thing in itself", it leads to a hatred of that deceitful "thing". This is the opposite of what icons are supposed to do!

Will's insight has whetted my appetite to learn more about the difference between these two views. He wrapped up our conversation with this blessing:

God bless as you wrap your brain around the 7th Council and a very "Unwestern" way of looking at images!

Blessings to all! Have a great Sunday!

*All Scripture quotes are from the King James Version unless otherwise stated.

(Source: BibleGateway. Image Source: WikiPaintings)

That is a wonderful look at the literature and how it opens up our understanding of the Second Commandment. You've illuminated truth to me once again, Adriana.

ReplyDeleteThanks,

Tim

I'm glad you brought up the 2nd Commandment, Tim. This adds even more depth to the discussion. I'm not sure I fully understand how any icon (realistic or not) could be used in light of it.

DeleteExodus 20:1-6

20 And God spake all these words, saying,

2 I am the Lord thy God, which have brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage.

3 Thou shalt have no other gods before me.

4 Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.

5 Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them: for I the Lord thy God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me;

6 And shewing mercy unto thousands of them that love me, and keep my commandments.

1) How do symbols like icons differ from symbols like letters?

Delete2) Do the images that letters and words create in our minds fall under the proscription of the 2nd Commandment?

3) If this was the meaning, why does God instruct the making of images in the Tabernacle? Golden Cherubim on the Mercy Seat, Pomegranates, and Palm Trees, not to mention the Horns of the Alter, and the feet of liturgical objects that are reported to be like those of lions?

4) Why are icons found on the walls of the oldest Synagogues we have discovered, liturgical images have been used in the Jewish community to this day (not just the symbol of the Star of David, but olive, grape, and fit trees, lions, and angels), and both the Catacombs and the Church of Dura Europos (not to mention the 3rd century cathedral of Armenia) all have extensive iconography?

5) Why is it that iconography was only addressed after 8 centuries by the Church, at the Second Council of Nicea, and after over 400,0000 Christians were slain by a Muslim-copying, government sponsored Pogrom?

6) Why is it that Dure illustrated the KJV (the best selling Protestant Bible ever) , Evangelical Churches use PowerPoint, and Protestants don't ban the usage of TV, family pictures, or the Internet? Why is it that Protestant Fundamentalists don't have a problem with Chick tracts, which use cartoons to teach children and functionally illiterate adults?

7) Why is there a difference in the Bible between the word "respect" (dulia) and worship (latria), both translated as "worship" in English? The Ancient Church understood the difference to be that of respect shown to things or people because of what they represent, and the worship that belongs to God alone. The Jews have always kissed the Torah before reading it, to show respect to the word of God, just as all the Orthodox Churches do today with the Gospel Books, crosses, and icons. Is this idolatry? Or, does it do as the Ancient Church professed, showing loyalty and respect to that which the objects represent?

Why do all Christians pray with their eyes closed (traditionally)? In the Old Testament, people prayed with their eyes open! The reason was that the Ancient Church tried to insure that those in worship never prayed to an image or a form, but to God alone. This is why the First Council dictated closed eyes. This tradition is still kept by most Christians, and especially by the ones who use images as a language into which the Gospel is translated.

9) The greatest argument that has been used by the Church, particularly by St. John of Damascus, in defense of the use of images for teaching, preaching, a d reminders of Christ's presence is the theology of the "Incarnation". In Moses' time, God had not circumscribed himself in the form of a man. God was not physical. But after Christ, God is and ever shall be, a man who has a physical body, a likeness, and a face. We do not claim that icons are that face - we necessarily proscribe the use of realism or of "graven images" (one of the reasons why the East never used statuary or carved likenesses), focusing on the physicality of Christ as a Man, and upon the inability of art to ever be Him, or masquerade as Him.

In Him,

Will